Italian energy consumers deserve better than an overlooked energy poverty policy and suffer from significant gaps in governance. The highly fragmented responses fail to prevent the increase of energy poverty and climate change issues. The current mitigation system is not enough to address the phenomena, and as suggested by the European Clean Energy for All package, efforts should be put in structured energy efficiency and long term consumer empowerment. The first victims of the fragmented responses are the households affected by energy poverty.

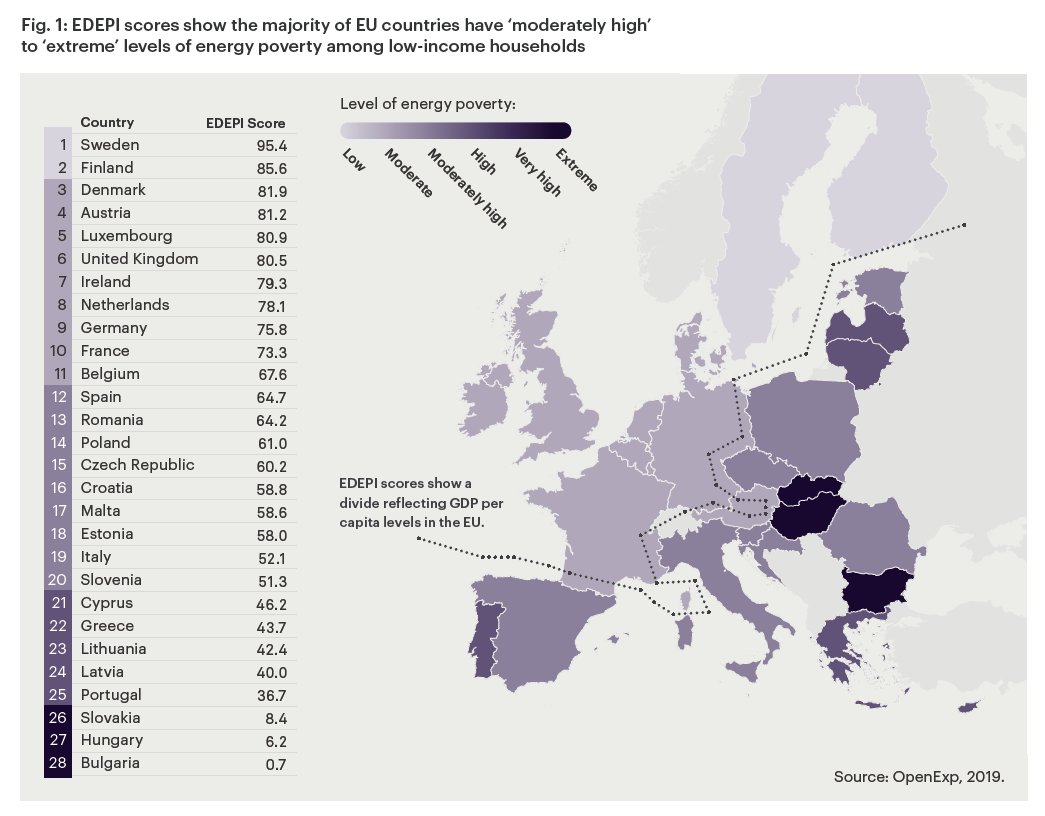

In a country where almost three out of four families own their homes, 10% of the households have difficulties to pay their invoices and accumulate debts with their electricity or gas suppliers, and 15.2% report difficulties to sufficiently heat their home. Meanwhile, the recent EDEPI index developed by OpenExp with the Right To Energy coalition shows the prevalence of summer energy poverty the country and the ineffectiveness of policies aimed at limiting the consumption in the housing stock, two points absolutely critical in understanding the social and environmental impacts of energy poverty. According to this index, in Italy, the problem of energy poverty is not so much about the energy expenditures as a share of total household expenditures, but mostly lies in the poor quality of the buildings (poor energy efficiency) and leaking roofs, leading to the inability to keep the home warm in the winter and cool in the summer.

A fragmented response failing to prevent the expansion of the phenomenon

Despite a very important number of energy suppliers, the market is still highly concentrated in the hands of the incumbent suppliers (ENEL and ENI). Regulated tariffs are still the norm, as the regulator postpones from year to year a complete market opening. Energy prices for domestic consumers in Italy are high due to the high level of energy imports and dependency on foreign sources. Extra costs, such as the tax on public television, are applied to the bills, creating misunderstandings, confusion, and mistrust in the market, adding a form of “functional analphabetism” and a massive disengagement of energy consumers.

The main measures addressing energy poverty, the electricity and gas bonuses, only impact bill payments and have little influence on energy poverty levels. If they represent a temporary relief for low-income families and people relying on life-saving medical equipment, they fail to address the inadequacy of the contracts, the poor quality of the dwelling and energy inefficiency. It seems, therefore, legitimate to question the level of public expenditure mobilised and the long-term sustainability of those measures.

Besides, the attribution of energy bonuses is too tedious, as the meager number of people requesting it from year to year clearly demonstrates. A draft law could lead to an automatic attribution, but some actors already warned of the burden on other consumers. The controversial “citizenship income” (Reddito di cittadinanza), entering into force in April 2019, could also lead to an automatic allocation of the bonus. However, the burdensome prerequisite to obtaining the income makes highly questionable that this measure will have the expected impact on poverty in general.

Wide regional disparities

All in all, the energy poverty issue is lagging at the national level. The creation of a national energy poverty observatory should only be launched in 2019, but the first insights have not implied coordination of the actors on the ground. The wide geographical and climatic disparities, the mistrust of the parties, the significant decentralisation and the general disinvestment of the State and the regulator lead to a fragmentation of responses and possible support for households in difficulty. Bits of answers are provided at the level of municipalities and regions, in collaboration with local companies, foundations, and associations. The technical answers provided are in general pilot projects implemented at the regional level (Banco dell’energia with A2A in Lombardy, Lotta alla Povertà energetica with Leroy Merlin in Piedmont, Tutor per l’energia domestica (TED) thanks to European funds in Rome and Milan).

Energy poverty and climate change are collective responsibilities

During the presentations I delivered on 28 February at the University of Turin in the framework of the Solar Seminar (Unesco Chair of Sustainable Development) and on 6 March at the Italian Parliament for the event “Luce sulla povertà energetica“, I insisted on two points: on the one hand, energy poverty is a complex phenomenon and a collective responsibility needing a strong engagement of all parties. Just as for climate, energy poverty will not be solved by a single technical, social, legal or regulatory, health, economic nor a financial solution. A financial commitment and a shared approach from public bodies and private companies are necessary in order to find long-term empowering solutions. The first victims of the fragmented responses are the households affected by energy poverty.

On the other hand, efficient and sustainable measures are bridging the protection of the climate with the emergency that represents energy poverty. Human lives aren’t siloed, solutions should not be either. It is critical to analyse the situation carefully and to encourage the search for preventive and not only curative solutions, involving all types of stakeholders. Energy poverty does not stop at people’s doorsteps. Only with a structured and integrated framework will we be able to respond to two of the major challenges of our time. As Commissioner for energy and climate Miguel Arias Cañete sums up, “the ecological transition will be socially fair or will not be”.

Resources

Find here the presentation I delivered at the Solar Seminar (University of Turin, 28 February 2019 – in English): Seminario Solars

Find here the presentation on Social and Climate Emergency: European examples, delivered at the event Luce sulla Povertà energetica (Camera dei Deputati, Rome, 6 March 2019 – in Italian) :Urgenza sociale e climatica, esempi europei

Find here my interview to CanaleEnergia: “Povertà energetica: “Bonus energia non basta, serve strategia integrata, preventiva e di lungo periodo”, 6 March 2019 – in Italian.

Find here the press release of the event Luce sulla Povertà energetica, 6 March 2019 – in Italian.